Uncovering the plot to save Earth’s ozone layer

Glasgow Science Centre's Shaun Edmond asks, "Why don’t we hear about the hole in the ozone layer anymore?"

Climate change has been the most pressing environmental concern since the late 2000s and was preceded by another issue that gripped the world back in the 1980s: the ‘hole’ in the ozone layer. But concerns about the ozone layer dropped off the radar of public consciousness. What happened to it? Well, this isn’t the usual story of an issue whose public awareness was but a passing fad, nor was it one of being overshadowed by a much larger problem. This was an issue that prompted swift and successful coordinated international action.

How the ozone layer works

Ozone is a colourless gas, composed of three oxygen atoms (whereas the oxygen we breathe contains two oxygen atoms). The ozone layer lies mainly in the upper stratosphere and it acts as a barrier to a certain type of ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the Sun. It’s vital for protecting life on Earth.

If not for the ozone layer, sunburn, and ultimately skin cancer, would be far more problematic and cataracts would be more commonplace. Entire ecosystems would be impacted, with aquatic life particularly at risk and crop yields likely to be significantly reduced.

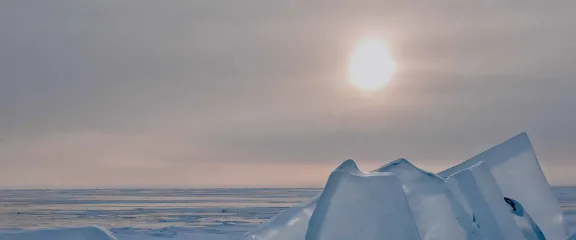

These issues are exactly what humanity faced when, in the 1980s, scientists discovered that atmospheric concentrations of ozone above Antarctica were rapidly depleting. They found that this was a regular occurrence: every year, around the Antarctic spring, the ozone layer above the continent was thinning further, creating a gaping hole.

The Montreal Protocol

The culprit was human-made compounds such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). CFCs were widely used in fridges, foam insulation and aerosol sprays. CFC gases slowly rise into the stratosphere where are they are broken down by the Sun’s UV radiation to release chlorine, which in turn, rapidly breaks down molecules of ozone. This depletion of the protective ozone layer allows the Sun’s harmful UV radiation to reach Earth unabated.

Scientists who had been studying the ozone hole presented their findings to the United Nations and in 1987 the Montreal Protocol was agreed. This treaty aimed to phase out the production and use of chemicals that were damaging the ozone layer. This would become one of the most successful pieces of international environmental legislation in history; it has now been signed by every country in the world.

While the ozone hole still appears around Antarctica every year, there is evidence that it has begun to shrink, and it is expected to recover to pre-1980 levels by 2070. Patching up the hole in the ozone layer is estimated to have prevented 2 million cases of skin cancer each year, as well as saving much of our planet from becoming uninhabitable by 2050.

Moving forward

The success of the Montreal Protocol is clear; the ozone layer is recovering. Could future me be writing a similar article on climate change? Touch wood.

Let’s start with the (slightly) bad news. Remedying the ozone hole was made possible since it was a relatable problem: the need to protect human health from UV damage and the resulting skin cancer and cataracts. There was also a single, easily identifiable problem, the use of chemicals that could be easily substituted with little cost. To be sure, large CFC manufacturers initially put up a fight, arguing that CFCs were perfectly safe. However, they eventually relented in the face of overwhelming scientific evidence - and more importantly, public opinion - to the contrary.

Tackling climate change, by comparison, doesn’t even skirt the bounds of simplicity. There are multiple causes and aggravations: deforestation, the melting of the ice caps, transport, fossil fuels, cattle farming. To say international collaboration has been difficult would be an understatement.

But, there is reason to be hopeful. If there’s one thing to be learnt from the ozone hole, it’s that the damage humanity wreaks upon the planet can be reversible, as long as there is the will and the effort to act. We’ve been able to track climate change and identify its causes, and efforts are being made to develop and implement solutions - however easier said than done, some of them may be.

The world must come together before we can do it again.

Further Information

Each year, to mark the anniversary of the treaty, 16 September is designated ‘International Day for the Preservation of the Ozone Layer’. The theme for this year is Montreal Protocol@35: global cooperation protecting life on Earth.

This blog post, written by Shaun Edmond from Glasgow Science Centre, is adapted from an article that first appeared in Glasgow Times in September 2022.